Placemaking in Historic Downtown Cheyenne Balancing Form and Function

PROPOSED ROAD RECONFIGURATION CONCEPT FOR LINCOLNWAY. GRAPHIC PROVIDED BY CITY OF CHEYENNE.

by Sreyoshi Chakraborty, AICP, Cheyenne, Wyoming

Cheyenne is not the newest kid on the block in trying to figure out how to make itself competitive in attracting an educated, creative, diverse and skilled workforce. For better or worse, this sleepy state capital is regularly compared to its better-known neighbors to the south Fort Collins1 and Boulder which have consistently ranked among the top small cities in the country.

During a recent workshop in Cheyenne organized by Smart Growth America, an interesting discussion ensued. A study2 conducted by Cheyenne LEADS, an economic development entity, concluded that approximately 22 percent of Cheyenne’s workforce commutes from Colorado. The question often asked is “who are these people and why would they choose to pay taxes in Colorado even though they work here?” The answer is complicated. More importantly, what constitutes a strong, attractive and vibrant community that draws and retains a creative class? Could a thriving downtown be key to this puzzle? Could planning potentially help in this process? It was amidst these challenging questions in 2012 that the Cheyenne Metropolitan Planning Organization embarked on a study to look at the historic U.S. Highway 30, known locally as Lincolnway, which cuts through the heart of downtown Cheyenne.

Lincolnway has a rich history of connecting communities across the nation as the automobile became ubiquitous. It was part of the Lincoln Highway, the original transcontinental highway, which celebrated its centennial in 2013. This route served as an economic lifeline for communities, and local and interstate commerce was focused around the nodes along the road.

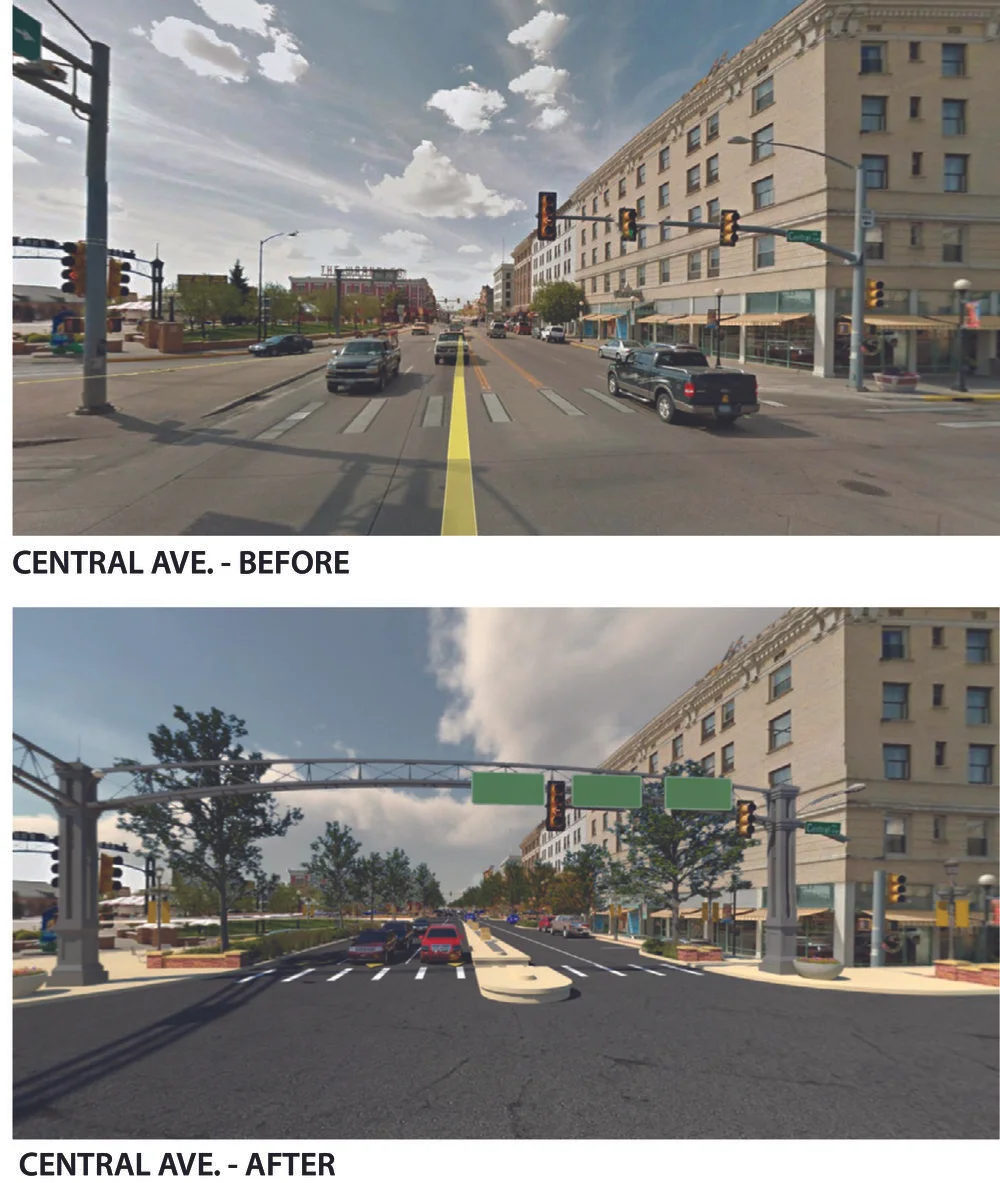

3D ILLUSTRATION OF PROPOSED CENTRAL AVE/LINCOLNWAY DESIGN. GRAPHIC PROVIDED BY CITY OF CHEYENNE.

Over time, as technology improved and speeds increased, the Lincolnway corridor in downtown Cheyenne gained additional traffic and speeds continued to increase. The historic storefronts built in the days of horse-drawn carriages and steam locomotives gradually faced the impacts of changing times. Slowly, commercial development pulled out of the center of town in favor of enclosed, climate-controlled malls on high-speed suburban roadways, leaving the heritage of downtown to fend for itself. A self-perpetuating process of declining business and pedestrian activity permitted drivers to speed through the core without concern or distraction.

People’s preferences have started shifting again, and a renaissance in downtown was envisioned and supported by the restoration of the historic Plains Hotel and the Union Pacific Railroad Depot. Public investment added a context-sensitive parking structure to support private reinvigoration of Cheyenne’s heart. The community was invited back downtown with the construction of the Depot Plaza, the premier gathering space for the city, attracting tens of thousands of visitors throughout the year. Life and vibrancy started returning to downtown.

Unfortunately, the tie that once connected our community to the rest of the nation has become a barrier that divides downtown Cheyenne. Traffic and speeds on Lincolnway make the adjoining buildings difficult to use, with conversations sometimes drowned out by the noise of engines and rumbling semi-trucks. Where pedestrians once window-shopped is now an area that has difficulty competing with the sanitized versions of downtowns.

The much loved Depot Plaza and the activities that radiate out from this community focal point have led to a conundrum for Cheyenne planners. In order to access the Depot Plaza and its events, people have to cross four lanes of traffic without a pedestrian refuge, and the crossing time is barely long enough to walk across. Little did we know that a simple and seemingly straightforward placemaking effort to look at the pedestrian and urban design elements in downtown would grow into a protracted planning process that was finally adopted in early 2016.

The challenge with this effort right from the beginning was walking the fine line of balancing the needs of downtown businesses, a major state highway, and the overall pedestrian experience. The initial intent of this study was to create a plan to help address the concerns impacting downtown Cheyenne’s transportation network, including roads, pedestrians, and adjacent land uses. In the end, the study included an expansive and detailed collection of traffic analyses and a suite of design and traffic recommendations that would be too big to address in one try. A phasing plan was ultimately more palatable to all stakeholders.

Compromise is not unfamiliar to planners. How many times have we come to a ‘compromise’ in order to reach a consensus on competing needs and interests? After all, it may not be the best option, but it is far better than no action. The recommendations within this Placemaking Plan take a slightly different approach that is broader and more realistic. The plan is organized into several phases and options, some of which are too unpredictable to pin down at this time. To discard ideas or possibilities based on current leadership, ideologies, politics, engineering standards and/or funding would be shortsighted and counterproductive.

The Wyoming Department of Transportation may not see the value of design improvements at the cost of a moderate travel time delay for drivers today, but that could be a moot point in the future. This resulted in an extensive design document that includes a menu of design and traffic recommendations including the option of a road reconfiguration from five lanes to three lanes, streetscape enhancements, alley improvements, landscaping, and signal timing modifications. The plan also provides spectacular visualizations through creative renderings, 3D modeling accessible through QR codes, and visual simulation of traffic reconfiguration illustrated via videos.

All of this may have taken the patience of a saint, but, in the end, the process and results were well worth the effort. With a robust plan in place, the city, as well as downtown stakeholders, have a valuable tool to turn some of these ideas into reality.

The author wishes to give special credit to Matt Ashby, former Cheyenne Planning Services Director, Russell + Mills Studio, Fehr & Peers, and DHM Design.

Sreyoshi Chakraborty, AICP, is a planner at the Cheyenne Metropolitan Planning Organization with a strong interest in providing safe and healthy transportation choices to people from all walks of life. She has worked as a planner for over nine years. Chakraborty is passionate about how the built environment and transportation options help with a community’s overall health and access to a good quality of life.

Published in the December 2016/January 2017 issue