Civilian Conservation Corps in Montana: 1933-1942

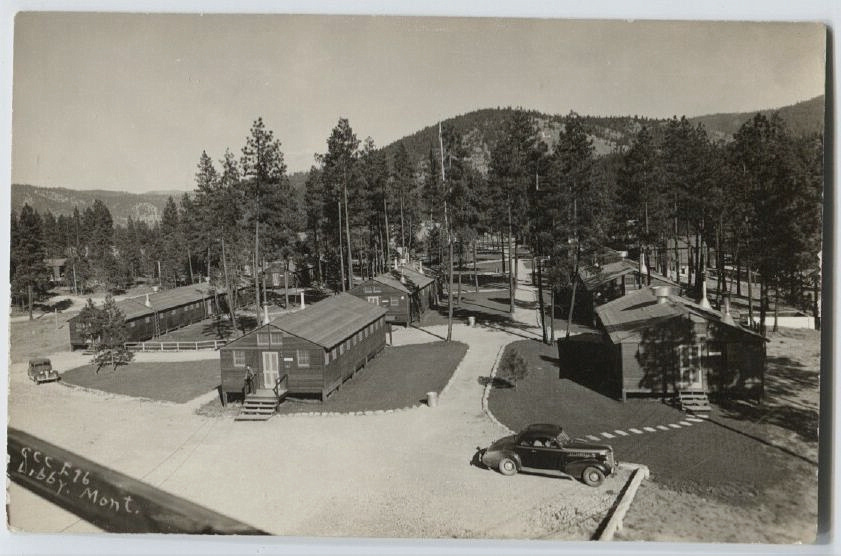

A U.S. Forest Service CCC camp In Libby Montana. Photo Courtesy of U.S. Forest Service.

by Michael I. Smith, CFM, Phoenix, Arizona

Though no longer unique in its approach, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) represents an early effort to coalesce the concepts of natural resources conservation planning with human resource planning.

Foresters and soil scientists, park planners and architects worked in conjunction (if not always cooperatively) with educational leaders, military men and labor groups (CCC director Robert Fechner was himself a former union leader) to take what was at the time our most vulnerable human asset and move that group into predominately rural settings where their efforts could be brought to bear in an effort to repair damage from decades of neglect or overuse and to open new areas for recreational use.

As a result, young men with few prospects from Eastern states found themselves working in the wide open space of places like Montana, improving streams and rangelands and building facilities to improve recreation; all the while doing so under the guidance of leaders and mentors – military officers, technical service foremen, surveyors, landscape architects and educational advisors (many of whom were unemployed as a result of the Great Depression).

The CCC was not perfect by any means – the opportunity was only open to young men, racial segregation was the norm and some camps gave a poor performance with respect to enrollee morale or work accomplishments – but by and large, the CCC produced a sustained record of accomplishment that will not likely be repeated on a national scale.

CCC in a Nutshell

The Emergency Conservation Work program – the ECW or Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) as it is more popularly known – sprang to life in the first 100-days’ of President Franklin Roosevelt’s first term in office in 1933. From a manpower management standpoint alone, the CCC was a colossal undertaking with camps and men moving from community to community and from state to state in accordance with work needs, the changing seasons, and even in response to the demands of local residents or politicians.

The plan called for the enrollment of young, single men, to work on forestry, wildlife and range management, conservation, and parks and recreational work in every state. An enrollee’s base pay was $30 a month, of which $25 was sent home to his family. Enrollees could gain promotion to assistant leader and leader positions and thus were given opportunity for promotion and better pay. The War Department was tasked with enrolling the men, and seeing to their care while in camp.

The Departments of Interior, Agriculture and Labor were generally given the responsibility of managing the men while at work sites, with each camp being designated based on the using agency in charge of the work. So for example, camps designated by the letter “F” were generally engaged in forestry related work on state or national forest lands, camps designated “SP” were situated in state or local parks, while “SCS” camps were tasked with work for the Soil Conservation Service. The CCC operated uninterrupted from 1933 until 1942 when funding was discontinued in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entry into World War Two.

CCC Projects in Montana

Streams are improved by the CCC. CCC enrollees working on stream improvements in Montana. This image appeared in The CCC and Wildlife, a Civilian Conservation Corps publication produced in conjunction with the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey in 1939. From the author’s collection.

Between 1933 and 1942 some 40,868 individuals worked on CCC projects in Montana, of which, 25,690 were from Montana. The balance of CCC enrollees who worked in Montana were young men sent in from out-of-state, most notably, New York, New Jersey and Kentucky. Nelson H. Spaulding enrolled in Alexander, New York in late April, 1934 and was sent to Fort Dix, New Jersey for in-processing. From Fort Dix, Spaulding was assigned first to a camp in Fredericksburg, Virginia where he participated in restoration work at the Civil War battlefield. In June 1934 the company was moved out to Glacier Park, Montana, where, after a five day train ride, the company was put to work clearing the massive burn area at the site of a devastating forest fire five years earlier. Ultimately, eight to ten CCC companies would undertake clearing and reforestation work in Glacier National Park and, as we will see, that was not the only CCC work undertaken there.

Elsewhere in Montana CCC camps were established at places like Lewis and Clark Caverns State Park near Whitehall where enrollees from camp SP-3 constructed a visitor center, park roads and improved access and amenities within the cave complex itself. CCC enrollees based at Camp Nine Mile in Alberton not only helped improve the facilities there, they also helped tend the livestock used by the nearby Lolo National Forest. The camp at Nine Mile became the staging camp for deployment of CCC enrollees across the state and, with the capacity to house 600 men it grew to be one of the largest camps in the country.

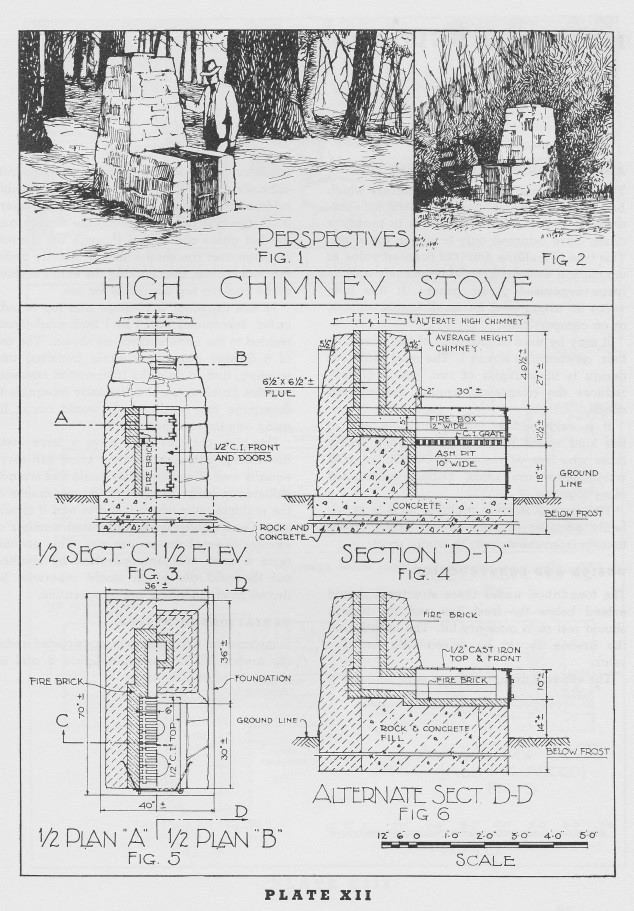

Camp stoves & Fireplaces. Diagrams from Camp Stoves & Fireplaces, a U.S. Forest Service, Department of Agriculture publication written by a consulting landscape architect and published by the Emergency Conservation Work/Civilian Conservation Corps in 1937. Readers familiar with campgrounds and recreational facilities in the National Forests and National Parks may recognize some of these types of structures. Indicative of CCC styles, these improvements may still be encountered, not just in Montana, but nationwide. From the author’s collection.

Certainly, the crown jewel in Montana’s CCC legacy is Glacier National Park, which received its first contingent of CCC enrollees in the spring of 1933. Over the next roughly nine years, 13 CCC camps would be home to some 29 company-sized CCC units working in the park. The work and the setting were sufficient to garner a visit from President Roosevelt himself in August 1934. In a guest editorial that appeared in the CCC’s national newspaper Happy Days, enrollee Bill Briggs noted that, “Even the surrounding mountains and green-clad pines must have sensed that a great man was in our midst. Never did they seem so majestic and grand.”

As previously noted, a large part of the CCC effort at Glacier was devoted to clearing snags from a devastating fire. Additionally, however, enrollees found themselves deployed in an effort to prevent further damage from wildfires and in reforestation work, trail building and construction of recreational facilities and stringing telephone line. The CCC work at Glacier was a microcosm of CCC work nationwide, where a pent up demand for labor meant a laundry list of chores that needed to be done.

Elsewhere in the U.S., it is estimated that the advent of the CCC moved work projects in our National Parks and Forests ahead by decades, and such is likely the case at Glacier National Park and many other locations across Montana. Among the responses elicited from Forest Service men in the Missoula Region for one of the last annual reports for the CCC program is this glowing appraisal of the CCC’s impact not just on the land but on agency thinking and process:

“Conservation projects benefited the forest lands. And there was a benefit too from the experience of handling the CCC undertaking to the Forest Service, as an organization, and individually. It taught us tolerance of the temporary shortcomings of those who could be taught how to do the things we wanted reasonably well. It emphasized to us the value of training employees in-service, and greatly stimulated the attainment of our present high order training policies. It helped us learn how to train.”

And this summation – again, from foresters serving in the Missoula Region - of the program’s importance in providing experienced managers in the initial months of the war when manpower was being siphoned off for the military and war industries:

“In our hour of national emergency when the demand for trained organizers is great, CCC has made direct contribution. A large percentage of the Forest Service on-the-ground managers are coming from the CCC by virtue of the experience and knowledge these men gained throughout the CCC programs…”

There seems little doubt then that the CCC was a boon to both the lands and the young men of this nation and to the state of Montana.

Community, Camaraderie, Citizenship

No discussion of the CCC would be complete without some mention of the sense of community that existed in the camps nationwide. At full strength a CCC company was comprised of 200 enrollees and the officers and foremen tasked with overseeing the camp and the work. Camps were very much like small towns, often fielding athletic teams and producing camp newspapers.

Among the enrollee-produced CCC camp newspapers in Montana were titles like The Drifters, produced by Company 280 in Augusta, The Cavern Echo written by enrollees from Company 574 in Whitehall and the Bitterroot Bugle, the camp newspaper for Company 1501 in Darby. Civilian Conservation Corps work and activities in Montana were reported on at the national level in the pages of Happy Days, “the authorized weekly paper of the CCC.”

Often such articles came from local enrollees who served as stringers and journalists in the field. Newsy in nature and nearly always with an eye toward the upbeat and didactic, some Montana related coverage in the May 30, 1936 issue of Happy Days included a story about the University of Montana’s offer of a one-year school of journalism scholarship to the editor of the best paper in the Corps area, with the winner to be chosen by competition. Elsewhere in the same issue was reported the news that the high school in Superior, Montana was the recent recipient of a 90-foot flagpole courtesy of CCC Company 591, presented in part to thank the students and townspeople for their many kindnesses. The August 17, 1940 issue of Happy Days included a story about Company 3568 in Bridger, Montana and the elaborate irrigation system they installed to keep their parade ground looking green and the July 20 issue that summer carried this glaring front page headline: “Thousands of CCC Men on Lines in West as Worst Fire Season Looms: Montana and Idaho Hardest Hit; 2200 More Fires Than Last Year; Fighters Get Supplies by ‘Chutes.”

Many eastern enrollees found themselves far afield of their beloved city life and their personal boundaries were stretched as they made friendships that in some cases lasted a lifetime and which, in at least one case, provided an adventure with a future star. Burton L. Appleton, an enrollee from New York, wrote at length about a particular camp mate who went by the nickname “Pro” in Company 3280 at Camp GNP-15. More than 60 years later many of the details remained fresh; in particular, an excursion he and his buddy took to Butte, Montana in 1939 where his companion convinced him that he could supplement their meager pocket money by playing a round of blackjack in a local gambling house. “Well, I never saw money disappear so fast! Literally, within minutes our stake was gone…I don’t think Pro won even one round.”Turns out, “Pro” went on to have a career in Hollywood; the enrollee they called “Pro” because he spoke like a professor, was none other than Walter Matthau.

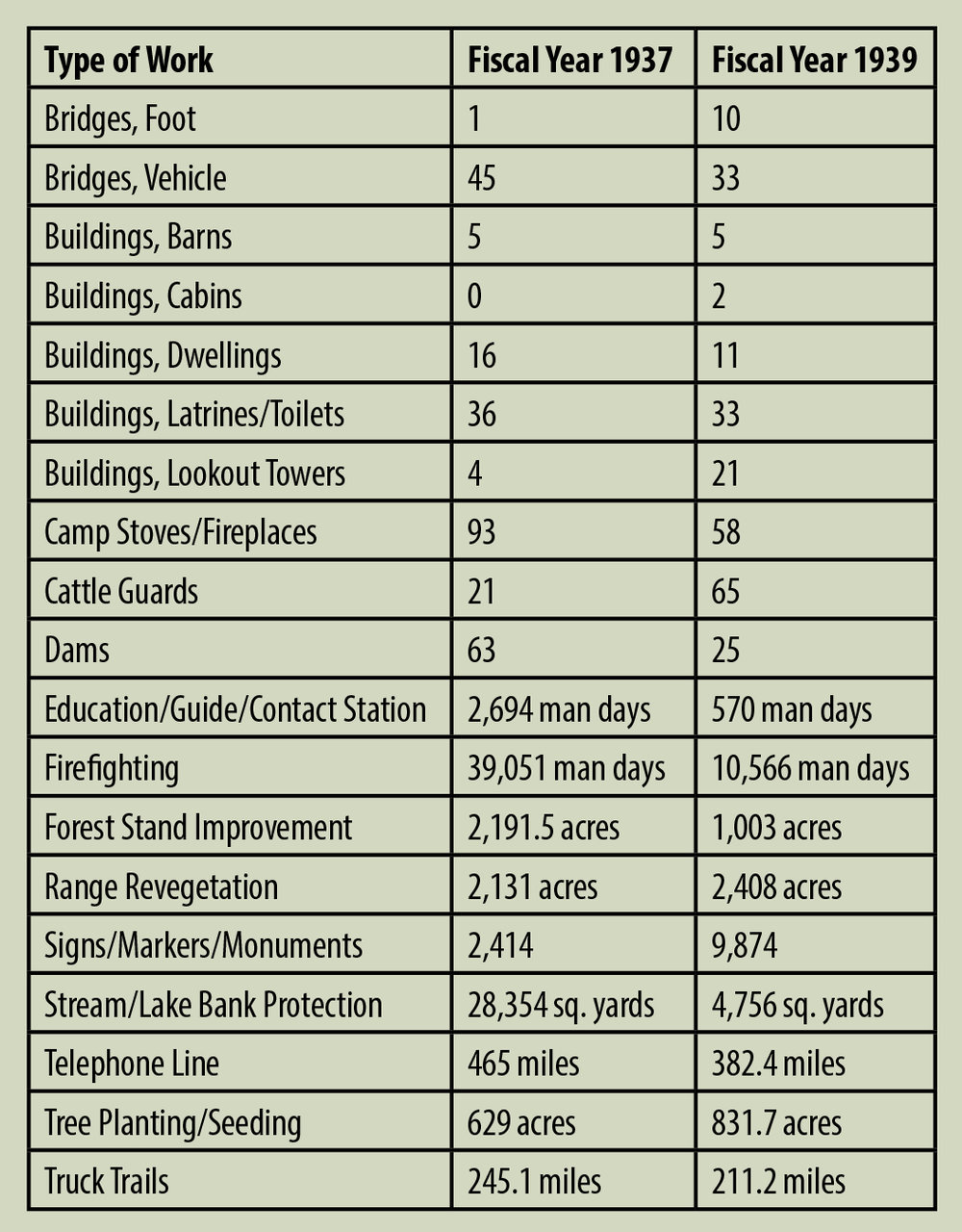

The tables and charts that appear with this article provide a glimpse of the end product that resulted from the effort put forth by the CCC in Montana, and the numbers of enrollees who benefited from the work whether working in Montana or simply having enrolled there. A less tangible but equally valuable result was the impact the program – and the experience of living in the woods and fields of a soaring Western state – had on the psyche and future outlook of the average enrollee.

In hindsight, perhaps some enrollees would find it ironic that just months after working in a peacetime forest army – perhaps farther from their home than they’d ever been - they would find themselves deployed around the globe in an effort to win a World War. No doubt many who survived that effort returned home with a renewed appreciation of life and an increased sense of pride and nostalgia for their peacetime effort in the forests and fields of this United States.

FREE TIME IN BUREAU OF RECLAMATION CAMP 57, BALLENTINE, MONTANA. PHOTO COURTESY OF U.S. BUREAU OF RECLAMATION.

Perhaps Life in the CCC Wasn’t Always A Thrilling Adventure…

Thousands of young workers came from near and far to perform useful work as CCC enrollees across the state of Montana in the 1930s. In hindsight, it can’t be said that every CCC enrollee looked at his time in the CCC with complete wonderment and satisfaction.

Nelson Spaulding, the enrollee from Alexander, New York, remembered a song that was popular among the enrollees with whom he served during his time in Montana:

In Glacier National Park

The home of the fleas

The home of the bed bugs

And the CCC’s

We sing loudest praises

And boast of its fame

While starving to death

On this government plain

How happy we are,

When the cooks go to bed

We hope in the morning

We find them all dead.

Admittedly, in this case the enrollee’s ire seems to be directed more at the cooks and the camp food.

A Snapshot of CCC Work in Montana

The Annual Reports included state-by-state totals for more than 150 specific work projects including construction of erosion control dams and various types of bridges, installation of telephone line and man-days spent fighting forest fires. The table below provides a snapshot of selected project types for the state of Montana for fiscal years 1937 and 1939. Bear in mind that these totals represent just two fiscal years in a program that operated from 1933 to 1942. Junior enrollees were paid $30 a month – roughly equivalent to $495 today - of which $25 was sent home to the enrollee’s family.

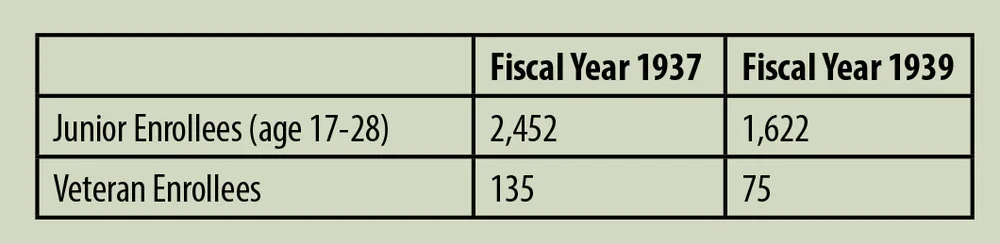

Selection of CCC Enrollees in Montana

The chart below provides enrollment totals for young men and veterans who enrolled in the CCC in Montana in fiscal years 1937 and 1939, regardless of where they ultimately worked. Over the lifespan of the Civilian Conservation Corps (1933-1942) 40,868 individuals worked on CCC projects in Montana, of which, 25,690 were from Montana. The balance of that total were young men sent in from out-of-state, most notably, New York, New Jersey, and Kentucky.

Montana Conservation Corps (MCC)

The Civilian Conservation Corps could rightly be called the parent of a number of modern-day organizations that strive to accomplish many of the same goals lined out between 1933 and 1942; though the birthing has often been a difficult one.

Without the urgency of a national economic crisis on par with the Great Depression, which saw roughly a quarter of the nation’s workforce unemployed, there simply hasn’t been sufficient impetus to replicate the CCC on a national level and some CCC boosters will argue with a fair degree of accuracy that the CCC will never be replicated in any event. Times just won’t be that bad again, folks say.

For that reason, the more successful latter-day manifestations of the CCC exist at the state and local level and Montana is no exception. The Montana Conservation Corps (MCC) (http://mtcorps.org/) fielded its first crew in 1991 and saw its budget double in 1993 when it obtained AmeriCorps funding. Today, watershed restoration, habitat enhancement, trail work and community service are among the project types listed on the organizations active resume, and, although cultural trends have evolved a great deal over the past 80 years or so, the original ethos of the CCC is never far removed from the big picture. Consider, if you will, the comments made by a CCC enrollee in 1934, compared to the comments made by an MCC crew leader in 2016:

“I love the woods now and everything in them from the fallen leaf to the tallest tree. I know when I emerge from these surroundings I am a better man in mind, body and soul.”

— Joseph Paul Jurasek, a CCC enrollee in Company 956, serving at Camp F-15-M, Coram, Montana in 1934

“I’d like to think one day the work I do on Montana’s public lands will lead someone else to realize, like I did, that all good things are wild and free.”

— Melanie Hobgood, MCC Field Crew Leader in 2016

But for the space of 82 years, young Paul Jurasek might easily have worked elbow to elbow with Melanie Hobgood, high on some Montana mountainside or grassy glade. Such is the enduring value of planning that considers both the natural and the human resource, don’t you agree?

Illustrations.

These are from Forest Outings, a U.S. Forest Service, Department of Agriculture publication edited by Russell Lord and produced by the Government Printing Office in 1940. From the author’s collection.

Michael I. Smith is a Certified Floodplain Manager and an Inspection Supervisor for the Flood Control District of Maricopa County, Arizona where he has worked since 1999. To access more of his research on the Civilian Conservation Corps go to: http://cccresources.blogspot.com.

Sources

- Appleton, B.L. (2004). A Montana CCC Adventure. NACCCA Journal, Vol. 27, Number 5, May 2004.

- Butler, O. (Ed.). (1934). Youth rebuilds: Stories from the CCC. Washington, D.C.: The American Forestry Association.

- Cornebise, A.E. (2004). The CCC Chronicles: Camp newspapers of the civilian conservation corps, 1933-1942. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Publishers.

- Davis, R. & Davis, H. (2011). Our mark on this land: A guide to the legacy of the civilian conservation corps in America’s parks. Granville, OH: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company.

- Federal Security Agency. (1942). Annual report of the director of the civilian conservation corps fiscal year ended June 30, 1942.Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Maher, Neil M. (2008). Nature’s new deal. New York: Oxford University Press.

- MCC. (2016, May 10). Building a better tomorrow [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://mtcorps.org/blog/view/building-a-better-tomorrow

- Merrill, P.H. (1981). Roosevelt’s forest army: A history of the civilian conservation corps. Montpelier, VT: Perry H. Merrill.

- Mylchreest, M. (2012). Images of the West: A Young Man’s Opportunity, The Civilian Conservation Corps of Montana. Big Sky Journal.

- No Author. (1996). The CCC in Montana. NACCCA Journal, August, 1996.

- Office of the Director of the Civilian Conservation Corps.(1937). Annual report of the director of the civilian conservation corps fiscal year ended June 30, 1937. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Office of the Director of the Civilian Conservation Corps.(1939). Annual report of the director of the civilian conservation corps fiscal year ended June 30, 1939. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Spaulding, N.H. (1994). CCC Unit Worked on Railroad, Restored Civil War Battlefield. NACCCA Journal, November, 1994.

- Strode, A.C. (1998). The Forest Soldiers in Glacier National Park. NACCA Journal. Vol. 21, Number 1. January 1998.

Additional Recommended Reading

While there are a number of excellent books that deal with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the following titles contain material that relates specifically to the work of the CCC, and in some cases, particularly work in the West:

- Audretsch, R.W. (2011). Shaping the park and saving the boys: The civilian conservation corps at Grand Canyon, 1933-1942. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing.

- Audretsch, R.W. (2013). We still walk in their footprint: The civilian conservation corps in northern Arizona, 1933-1942. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Press.

- Brown, R.C., & Smith, D.A. (2006). New deal days: The CCC at Mesa Verde. Durango, CO: The Durango Herald Small Press.

- Hinton, W.K. & Green, E.A. (2008). With picks, shovels & hope: The ccc and its legacy on the Colorado plateau. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company.

- Kolvet, R.C. & Ford, V. (2006). The civilian conservation corps in Nevada: From boys to men. Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press.

- Melzer, R. (2000). Coming of age in the Great Depression:The civilian conservation corps experience in New Mexico, 1933-1942. Las Cruces, NM: Yucca Tree Press.

- Moore, R.J. (2006). The civilian conservation corps in Arizona’s rim country: Working in the woods. Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press.

- Otis, A.T., Honey, W.D., Hogg, T.C. & Lakin, K.K. (1986) The forest service and the civilian conservation corps: 1933-1942. United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service. Retrieved from: http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/ccc/ccc/index.htm

- Salmond, John A.(1967). The civilian conservation corps, 1933-1942:A new deal case study. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Purvis, L.L. (1989). The ace in the hole: A brief history of company 818 of the civilian conservation corps. Columbus, GA: Brentwood Christian Press.