Tips for small towns airports and land use decisions

Photo by Kyle Slaughter

by Kyle Slaughter and Paul Moberly, Salt Lake City, Utah

While the term “airport” typically conjures up images of international airport terminals and giant 737 aircraft, the majority of airports across the western U.S. are small, rural airports—in Utah for instance, 39 (or ~85 percent) of the 46 operating airports are small airports located in rural counties.[2] As growth continues spreading from high density cities into traditionally rural areas, land use surrounding airports will become an increasingly difficult challenge for communities lacking staff capacity and land use tools to protect residents and airports from contiguous, incompatible uses.

“In Utah, For instance, residential growth across the Wasatch Front coupled with poor airport planning played an important role in many of the 123 Utah airports that have closed since 1974. [2]”

Land use decisions surrounding airports in these growing or soon-to-grow rural communities will be critical to protecting their long-term economic and transportation related health. Communities that adequately protect property owners from the impacts of an airport and the airport from incompatible use encroachment will experience the benefits of an airport that can meet local needs. Communities that fail to prepare will either deal with ongoing conflict between residents and the airport or lose their airports altogether.

Photo by Kyle Slaughter

Utah’s communities have experienced many of the challenges that accompany land use decisions around airports. Illustrative of these challenges, the mention of a local airport in multiple Utah counties can spark a heated debate between residents and airport sponsors with respect to denied building permits, altered runways, and subdivision requirements. Due to the long-term planning horizon required to protect airport uses, complex FAA regulations, and overlapping jurisdictions, planning for rural airports can pose unique challenges for staff with little understanding of these specialized land-use requirements. The following is some advice and techniques gathered and compiled in the guide: Airports & Land Use, An Introduction for Local Leaders. This guide was developed for use by Utah counties and municipalities, but has broadly applicable best practices for communities across the West.

ADVICE FOR AIRPORTS

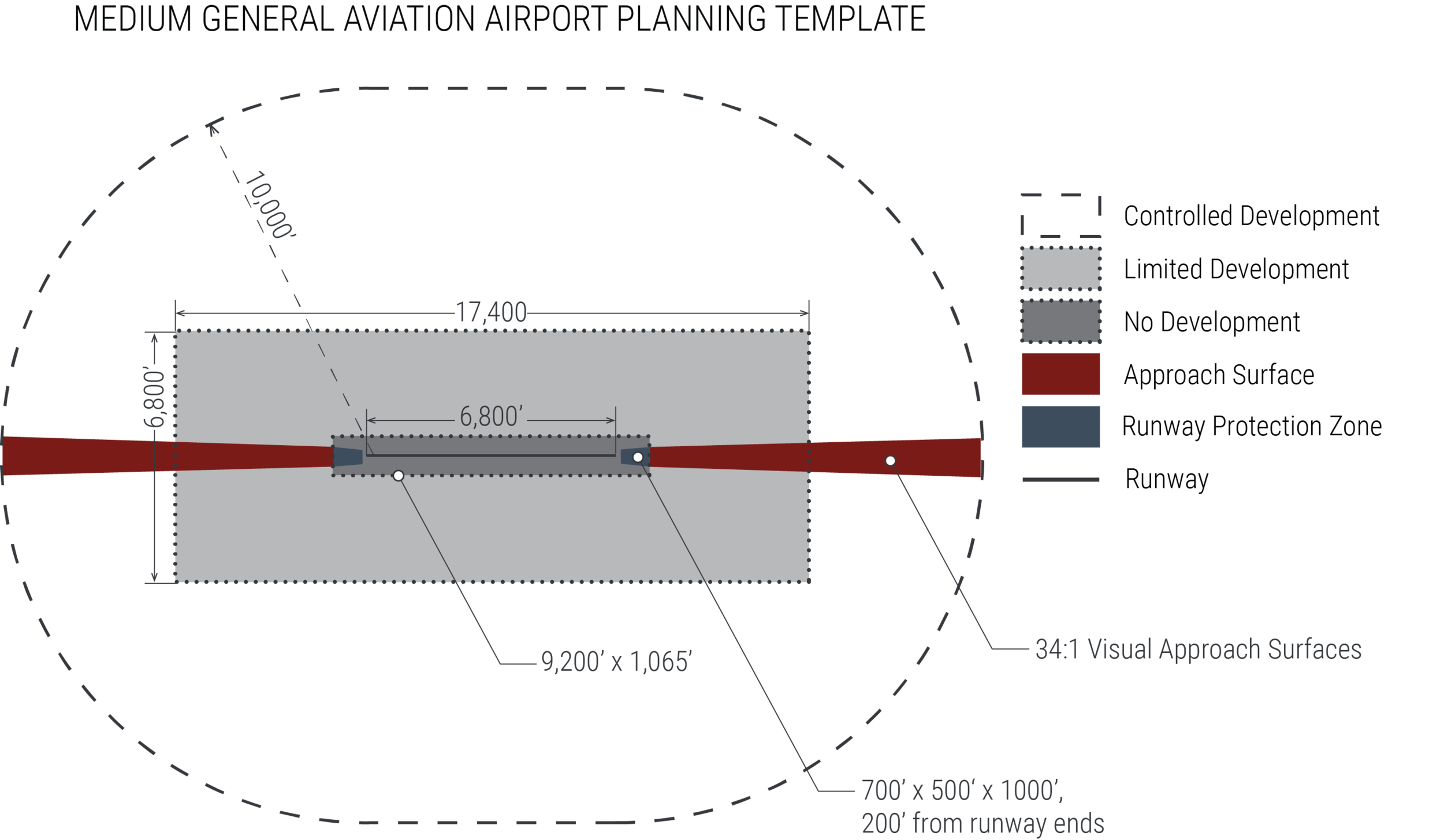

One approach used in Utah has been the adoption of a standard set of development overlay zones (see diagram above), which define appropriate uses and protect airport use and safety.[1] These standard zones are differentiated for three different sizes of airports: small, medium, and large (see table below). These zones have an associated land use matrix that clearly outlines approved, conditional, and prohibited uses in these areas. They are also intended to meet and match FAA regulations and recommendations.[2]

Overlay zones are the most appropriate method to regulate the land around airports. Overlay zones are sets of additional standards or requirements that are applied over the top of current zoning. These types of zones allow leaders to maintain consistent traditional zones, while ensuring requirements for specific areas are met before development can occur. Overlay zones are recommended in the case of airports for four primary reasons:

- An overlay zone still allows the zoning underneath to change while still protecting residents from potential negative impacts of the airport.

- It reduces the workload for those developing the zoning regulations by simply adding on to the current zoning structure rather than creating entirely new zones.

- While initially more complex, overlay zones are overall much simpler for land owners and residents, because there are a set of standard requirements that do not change, no matter how the underlying zone changes.

- Finally, because overlay zones are only applied to specific areas and maintain the underlying zoning, they can be more politically feasible than creating multiple new zones.

Source Utah Department of Transportation Aeronautics Division

Source Utah Department of Transportation Aeronautics Division

Plan ahead. Way ahead.

Airports are generally long-term assets, whose viability is determined by decisions made decades before population growth encroachment or other challenges arise. Most airport master plans establish goals and priorities for the upcoming 25 years, while the plan itself is updated about every 10 years. These plans consider airport growth, new or extended runways, and potential land purchases for the property directly contiguous to current and future runways. However, when considering land use around an airport, a much longer view—even 50 or more years in the future—is needed for establishing uses that will protect residents’ safety and allow proper function of the airport.

As a result of this long timeframe, community leaders have to seriously consider what their community would like to become, what it is likely to become, and how internal decisions and outside forces will affect the community’s final outcome while preparing for their airport’s future. This means looking at relevant growth projections, economic development trends, community goals, and considering how the community airport fits into those community trends and ambitions. In some cases, these considerations will lead to a conclusion that things should simply remain the same, or may even call into question the value of the airport. This information can assist leaders in making land use decisions around the airport that can avoid incompatibilities before they start.

Leaders should consider what their airport could become in the near- and long-term, then determine if they should regulate the land to protect for the possibility of expansion in the future. Depending on community aspirations and probable futures, it may be most appropriate to prepare to maintain a small airport or even expand to a medium or even large airport. Taking current property owners rights into account is vital; communities should discuss possibilities as a community and with the FAA.

Leaders should first consider the airport’s current size, followed by the intended runway size (information on planned expansions in the next 15–25 years should be available in the airport master plan, while expansions in a longer time frame will require assessment from leaders). The estimated maximum airport size should be the guide on zone sizes and regulation. This ensures that when the airport does expand, it will not have significant negative impacts on residents. Where expansion is not likely for decades, but leadership would like to retain the possibility of expansion, interim uses can be allowed certain uses in the short term with assurances from landowners that the use will phase out over time. These protect plausible expansions and property owners’ rights.

When cross-jurisdictional boundaries exist, build unity with boards

Photo by Kyle Slaughter

An airport’s master plan is completed by the airport sponsor—the city, county, company, or individual responsible for the airport—and land use surrounding the airport is the responsibility of whatever jurisdiction encompasses that property, county, or municipality. To avoid conflict, communities should define upfront how land use decisions surrounding the airport will be determined, considering current jurisdictions and potential annexations.

Cross-jurisdictional conflicts are typically limited where the areas surrounding the airport are wholly within one boundary: the planning commission makes recommendations to the legislative body who adopts, alters, or rejects the recommendations. However, frequently the surrounding lands are the responsibility of multiple city and county jurisdictions (or are within their planned annexation area). In this situation, each community maintains zoning authority for the area within their boundaries, which can cause a potential patchwork of conflict and confusion.

To avoid such issues, the Utah State Legislature passed the Airport Zoning Act which provides the option to create a Joint Airport Zoning Board. The commission requires “two representatives appointed by each political subdivision participating in its creation,” and provides the commission with authority to “adopt, administer, and enforce… airport zoning regulations for the airport hazard area.”

There are benefits and drawbacks to joint boards. Boards provide shared decision making by all affected jurisdictions, help increase zoning consistency for residents and property owners, streamline regulations, reduce political pressure on individual communities, and create a mechanism to deal with cross-jurisdictional conflict by forcing communities to create mutually agreeable terms. In contrast, joint boards may delay rule creation or frustrate those unfamiliar with the concept of an airport zoning board or who greatly value local control. Boards also carry with them their own set of political conflicts. Ultimately, it is up to the airport sponsor and entities with jurisdiction in the airport hazard area to determine when and how to handle regulations around an airport.

Keep the Land Use Toolbox Handy

In addition to overlay zoning, there are other land use tools available to protect airports and residents. These tools are either cooperative (working with landowners to achieve mutually acceptable arrangements) or unilateral (government taking action without consent from property owners). Additional governmental tools exist. The best way to address issues is using a mix of available options that match your particular situation. This list of tools is available in the guide; none of the tools are revolutionary, rather they are applied with the special considerations of an airport in mind. See http://ruralplanning.org/assets/airport-land-use-guide---web.pdf (page 10).

Remember the Golden Rule

Residents of small communities may question the importance of protecting small, rarely used airports, or be unable to fathom their tiny airport having long-term, major impacts on the quality of life for their community. Leaders working to protect their airports should give special consideration to maximizing property use options for affected landowners. Particularly in small towns, private property rights are cherished and efforts should be made to acknowledge and maximize land owners rights. Application of a wide range of planning tools will help enable landowners to have input in their land’s future and can optimize their land’s uses while protecting current and future airport use. In addition, full public transparency and engagement will help property owners understand why protective actions have to be made. There may still be conflict, but honest, open, upfront, respectful dialog over time will help resolve conflicts and lead to a sustainable airport surrounded by compatible uses.

Resources

- Utah Department of Transportation Aeronautics Division. https://www.udot.utah.gov/main/uconowner.gf?n=200703070613563.

- Wasatch Front Regional Council. Mountainland Association of Governments. Utah Division of Aeronautics. “Compatible Land Use Planning Guide for Utah Airports.” 2000. https://www.udot.utah.gov/main/uconowner.gf?n=200411180926131.

Endnotes

- Compatible Recognizing local airport land use challenges, in the year 2000 the Mountainland Association of Governments and Utah Department of Transportation Aeronautics Division teamed up to create the “Compatible Land Use Guide for Utah Airports.”

- See Appendix B of the “Compatible Land Use Guide for Utah Airports”

Paul Moberly and Kyle Slaughter are Consultants with the Rural Planning Group. Moberly’s professional focus is on community and economic development. Slaughter’s background is in public administration and private sector consulting. Both serve on the Editorial Board for The Western Planner.

Rural Planning Group

The Rural Planning Group (RPG) is a creation of the State of Utah’s Community Impact Fund Board (CIB). The CIB obtains funding from mineral lease royalties on extractive industries operating on federal lands. These funds are collected by the federal government and then returned to the state, the State returns a portion to CIB for use in rural communities. The CIB disburses this funding to communities that are affected by mineral resource development on federal lands. Visit www.ruralplanning.org.

Published April 2018